CHINAMPAS nEXT REGENERATION

The New York City drinking water supply system is the largest in the United States; it provides over 1 billion gallons of water to the city that comes all along 125 miles from the western regions. But this enormous travel isn’t happening because there’s no water in New York, but because their water is polluted.

One of the best examples is Gowanus Canal, in Brooklyn, which has been polluted over more than 150 years and is practically considered as Brooklyn’s dump.

This is not a local problem, either. Mexico, where we come from, as well as other countries experience the same situation with their own water bodies. To understand the problem better, we decided to study one of the most polluted rivers in Mexico: the Atoyac River, which runs through similar problems to the Gowanus Canal, not only contamination but also flooding.

We mapped, made mockups and studied it, but after a long research process, we realized that the greatest difficulty for these water bodies is the perception that people have of them.

Today, these rivers are seen only as garbage dumps, which has allowed the level of pollution they currently have and it is very ironic. We are grossly wasting a resource without which we could not live. So, how could we change this perception to begin to value it?

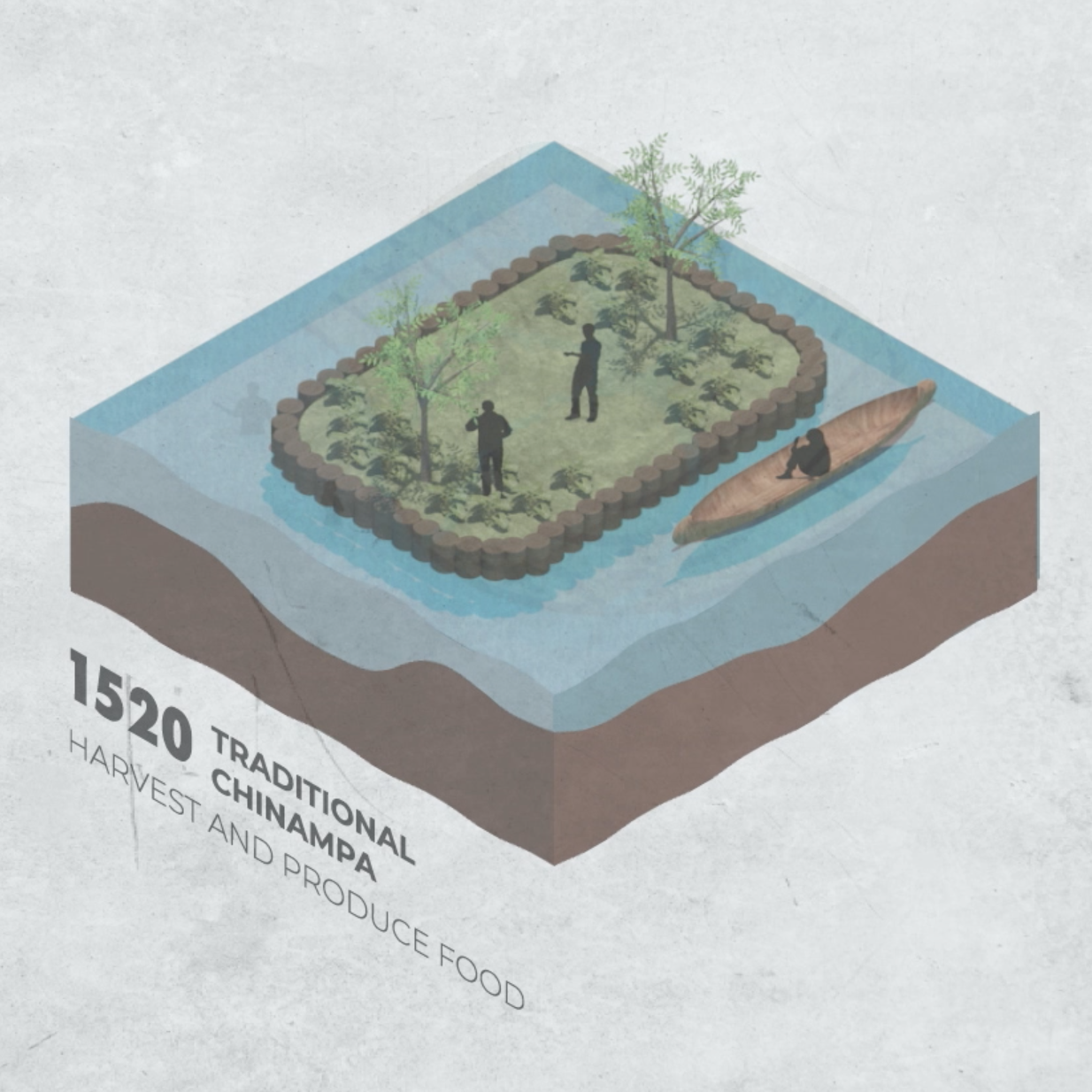

We began to study systems with which we could bring people to reconnect with the river and not just decontaminate it. Finally, we decided on the chinampas: a millenary system, found in Ancient Mexico, which based the entire functioning of cities on water.

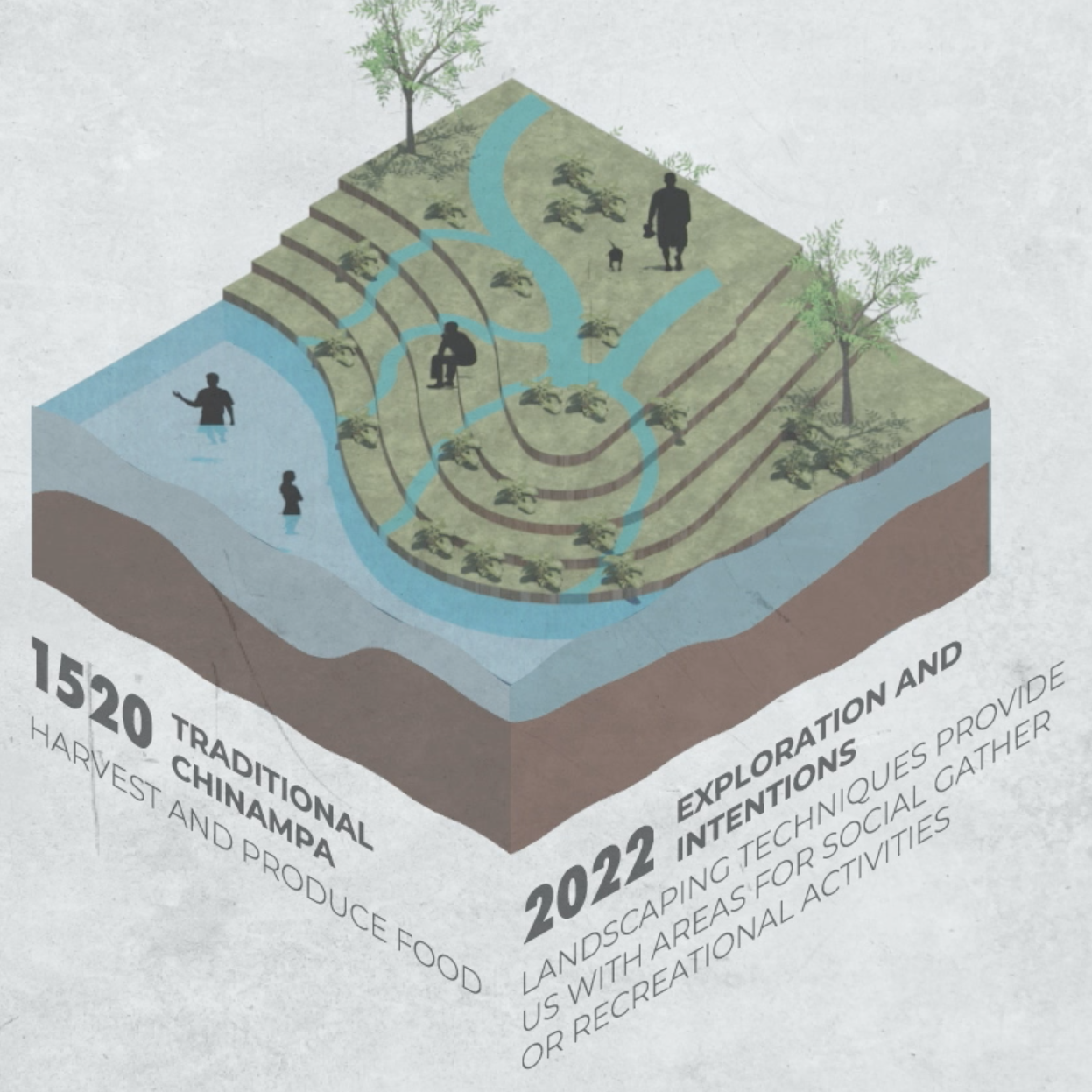

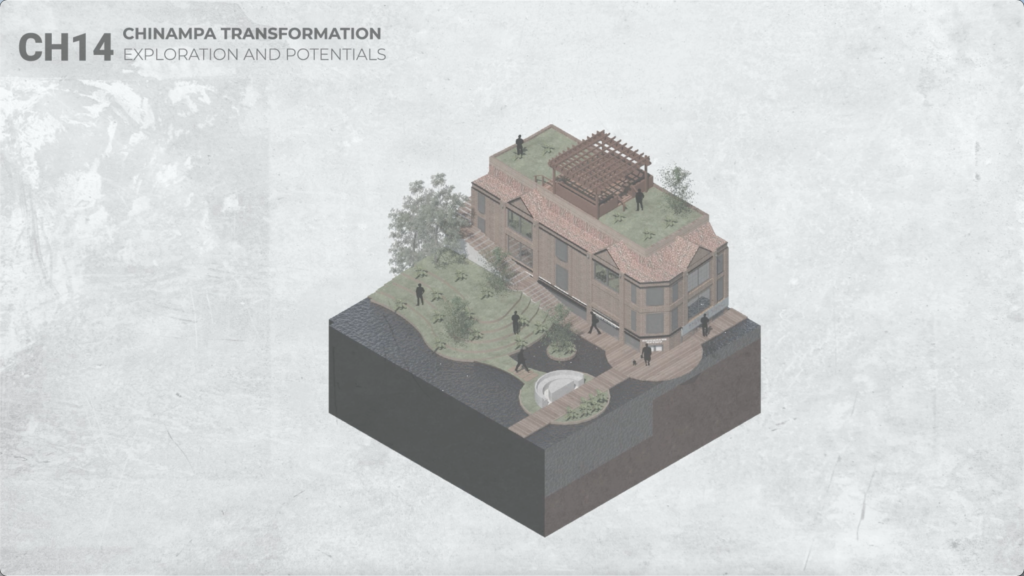

The chinampas are fields above water in which vegetables and flower’s cultivation are possible, allowing all year’s production, as well as continued ground’s renovation, water retention, even bioremediation. But beyond its structural and functional benefits, the chinampa’s importance consists in its capacity of opening spaces and offering an extensive list of activities.

That’s why for our project, we rethought this system and converted not only in a way of remediating water or cultivating vegetables, but also into a whole plan for revitalizing social structures through an intervention in the neighborhood.

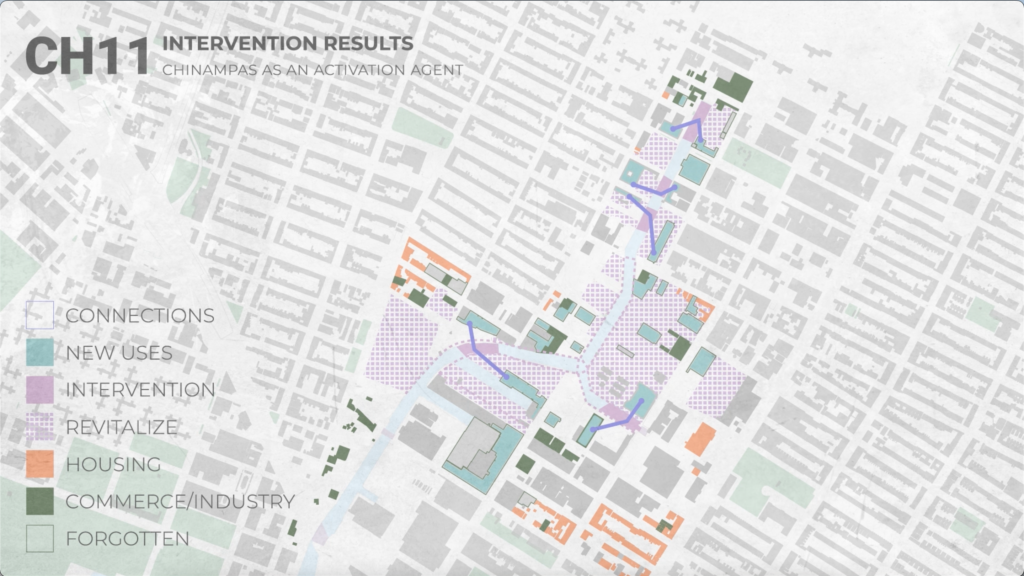

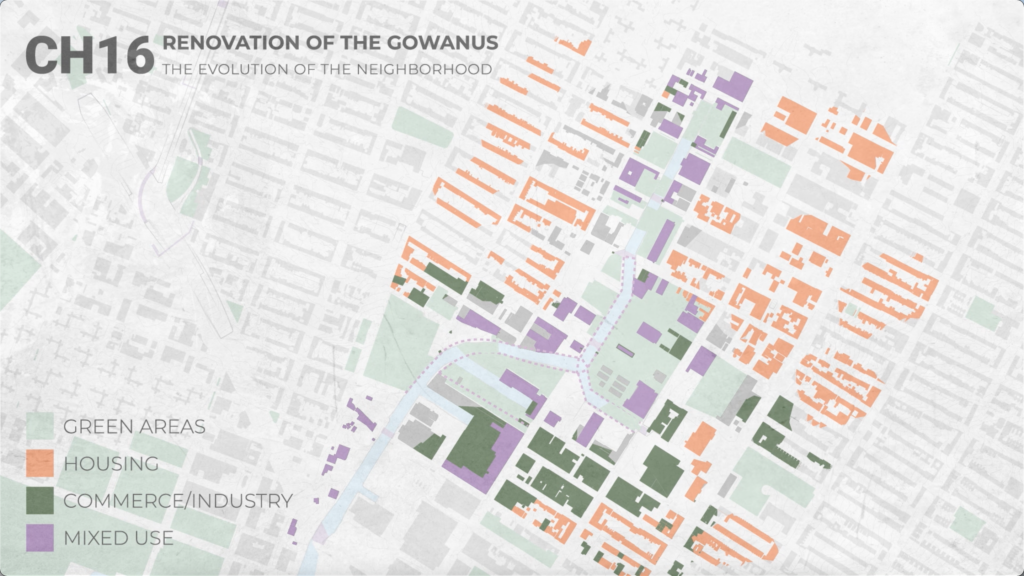

Our project proposes the use of existing spaces, along with the generation of new spaces to connect the Gowanus Canal with people.

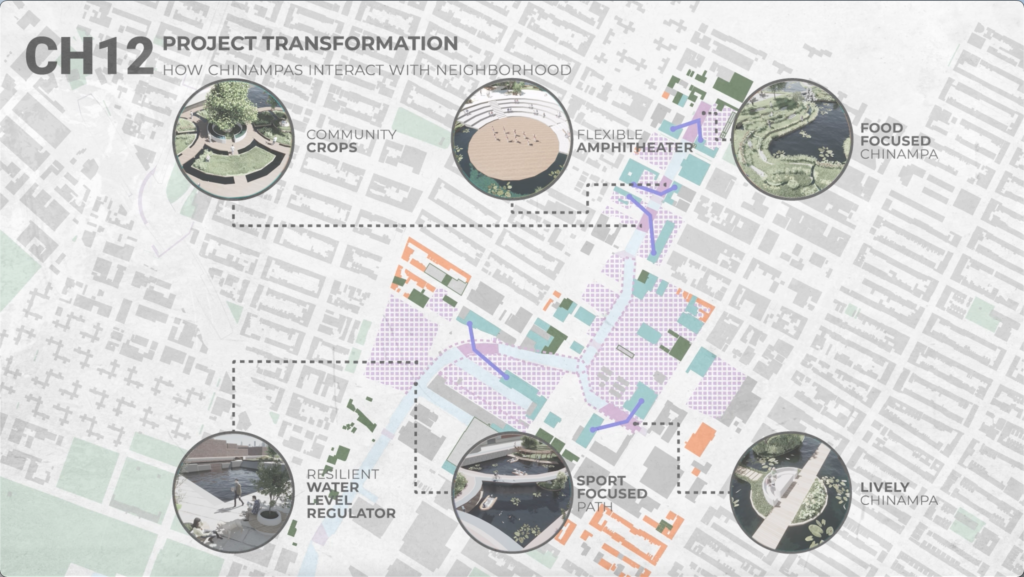

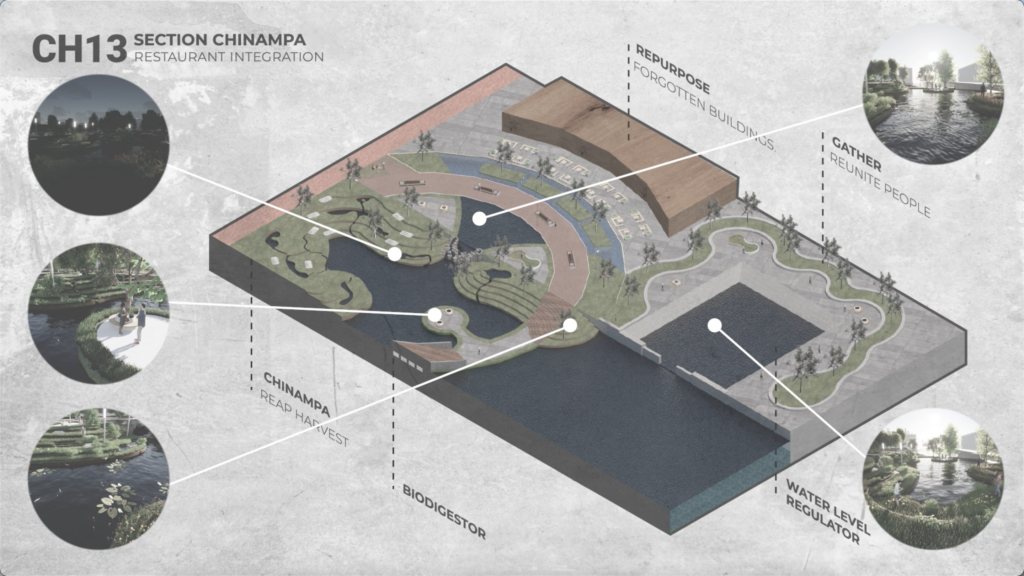

There are six interventions: a cultivation area for existing restaurants and the possibility of opening new ones; a cultural area, seeking to reform the building for an auditorium and opening spaces for outdoor presentations; residential crops for near houses, a bicycle path, a walking path made of circular chinampas, and resilient water level regulators.

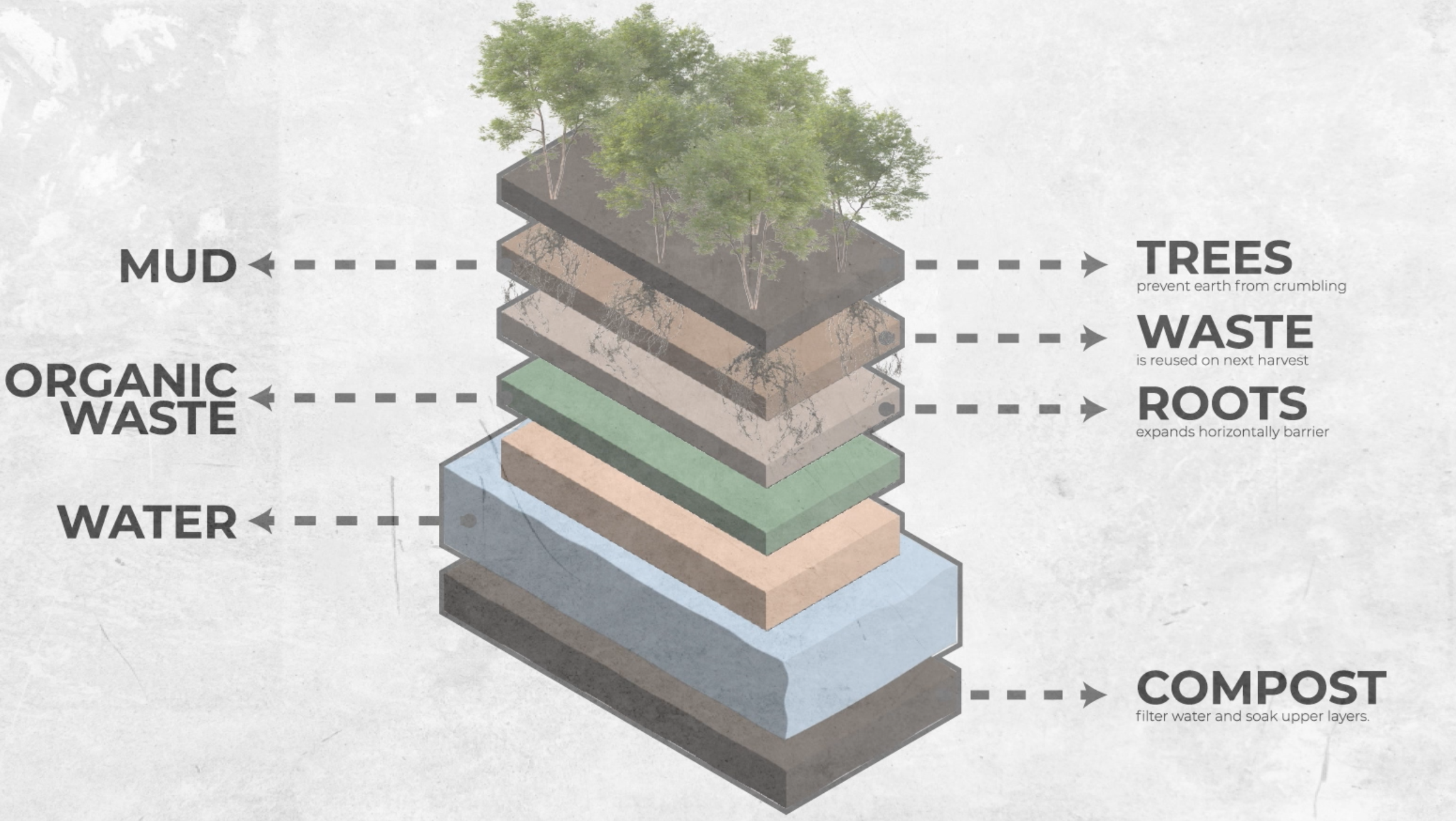

How does a chinampa work?

Easy. It takes the polluted water, which passes through a biodigestors barrier and becomes part of an artificial lake; at that time, water finishes of being cleaned by the chinampa’s ecosystem. All along, we also have the water lever regulators, spaces that gathers rainwater and prevents flooding.

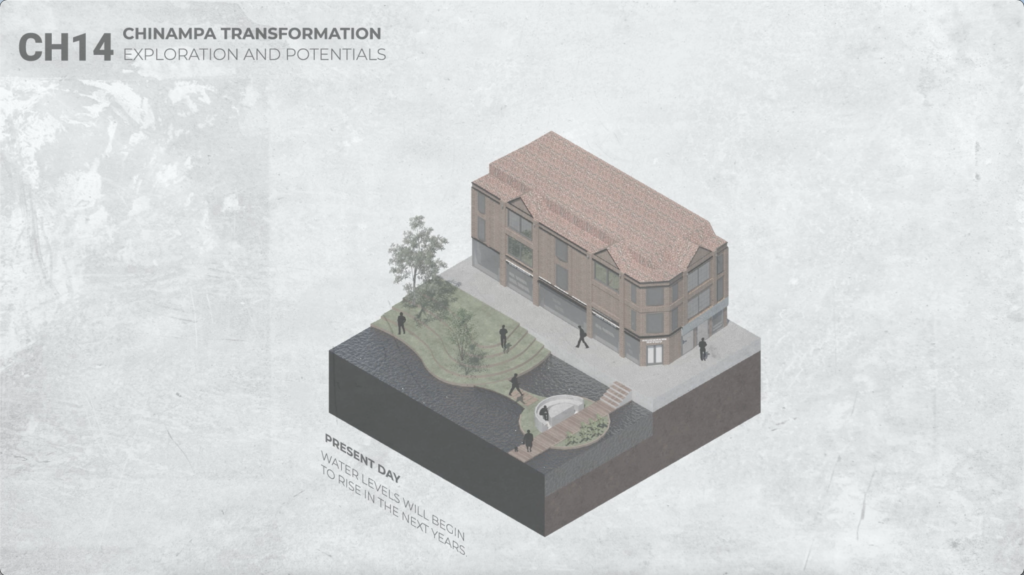

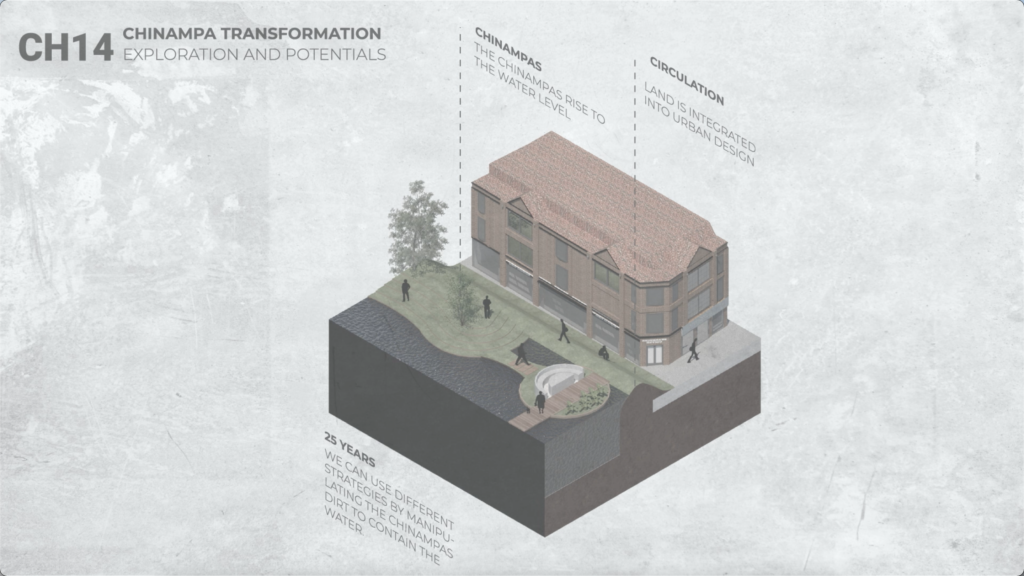

But even if water overruns its limits, the project would still remain: the chinampa is a floating structure and has no limits for growing at the same time as water level, becoming part of lanscape and even an elevated bridge between the canal and people.

BUSINESS MODEL

So, how can this become possible? For our project, we have three ways of financing:

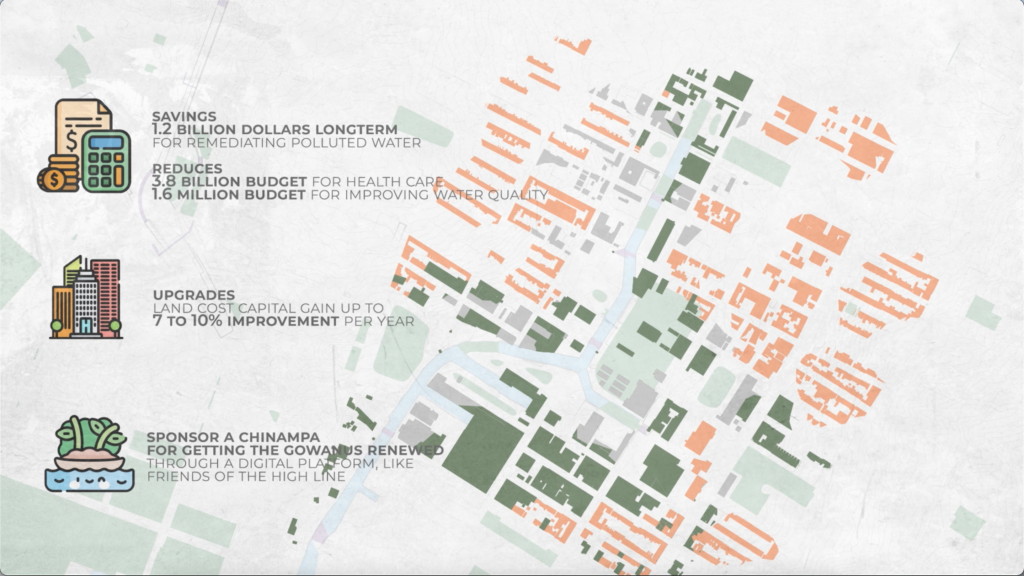

1.-A project like this, makes people more aware of the canal’s importance. For the Government, not only it would prevent spending 1.2 billion dollars for remediating polluted water in thirty years, but would also reduce the 3.8 billion budget for health care and the 1.6 million budget for improving water quality.

2.-The project would lead from a 7 to 10% capital gain for investors, with the savings on the budget we look forward to repurpose capital for affordable housing for people from the Gowanus.

3.-Finally, through a donation platform, people and sponsors could get information about the project and sponsor a chinampa, for getting the Gowanus Neighborhood renewed, like the Friends of The High Line case.

It’s time to face this problem and become part of the solution. As humanity we must reconcile with our supply sources through scientific and common participation, while remaining open to techniques that have proven efficient and sustainable.